|

-

6th August 08, 09:49 AM

#1

Soldiers Cheat

Soldiers cheat. I don’t mean that in a disparaging way, but I bet it got someone's attention - and, in case anyone's wondering, I spent my years in the regular army establishing a 'right' to a place in the sun.

I’m thinking specifically about kit, and more particularly about the fèileadh mòr or Great Kilt.

Anyone who’s been in the service knows that there’s what is required by regulations, and then there’s what the soldiers actually do with it.

Take boots, for example. Any soldier who’s passed out from basic training and proceeded to his battalion will have ‘acquired’ something like three or four pairs of boots, even if the quartermaster only issued him with two pairs.

There’s the everyday working pair, kept well-enough bulled to keep him out of trouble with his platoon sergeant and the company sergeant major. There’s the field pair – frequently non-regulation, and often civilian specialist boots (for a while in Northern Ireland the favoured boots were Hi-Tek Trail, suitably blackened; and for Arctic deployments Scarpa Manta boots were preferred over the issue ski-march ones) - and usually with high tops. Then there’s the pair that is produced for inspections: they usually live in the locker covered with a cloth, and have many, many hours of spit and polish devoted to them. And if one is a Woodentop – oops, sorry, Brigade of Guards – there’s a pair of drill boots: World War II vintage ammunition boots with metal studs.

And berets and bonnets. There’s an arcane ritual required to make them fit properly. Supposedly one could be put on a charge if officially caught doing it, but everybody does it (and the Platoon Sergeant will unofficially make sure it’s done) and once it’s done nobody bats an eyelid.

And so it goes on. There was the trick of running a bar of soap down the inside of the creases of trousers, shirts, and blouses before pressing them so that they stuck and looked sharp.

And Personal Load Carrying Equipment. Some of the stuff that was procured by MoD Procurements Executive was awkward to wear in the field, and sometimes even positively dangerous (e.g. 1958-pattern large pack). So things got done to it. And still do.

And then there’s what goes into it. Regulations require a longish list of items that have to be carried. Most of these are rarely used, and the weight and space in the Bergen could be better taken by things that will really, really be needed – like food and ammunition (and more ammunition) - and so they get left behind. And there’s the mania for miniaturising cooking utensils, normally by buying civilian backpackers' ones.

I imagine this has been done by the soldiery down the ages.

The Roman legionary’s gladius was worn on the right hip and drawn vertically. This limited the blade length to about eighteen inches. I’m sure there was many a long-service triarius who ‘acquired’ a cavalry spatha, had the blade cut down by the armourer, wore it on the left side using a cross draw, thus giving himself an extra six inches of blade – very useful in a close-quarter battle.

What’s the point of all this? Well, basically, as I mentioned, it has to do with the fèileadh mòr.

There are various suggestions about how to put on the Great Kilt, and how to wear it, and quite a lot of stuff on the internet that tries to be helpful. However, there’s the perennial problems of pleating, how to wear the ‘train’ in the most satisfactory manner so that the bulk of it is carried conveniently and it looks smart enough, and doing this without needing a Victorian-sized sitting room floor. None of these seems to me to have been addressed clearly in ways that satisfy - or, rather, satisfy me. So I wondered how the soldiers of the various highland regiments in the 18th Century - when they still wore the fèileadh mòr - dealt with the matter.

The essential problem facing an infantryman is how to look smart and regimental, and how to do that quickly and with limited space to hand. Speed is of the essence whether it’s getting on parade or standing to. So, they’ll have cheated.

I’d bet that fairly early in his service, Jock acquired an extra fèileadh mòr for inspection purposes which met all that the regulations required. Then there was the one that he actually wore.

The need to look smart and military will have trumped how he would have put it on at his croft (say, like in Robert Griffing's "The Jacobite" - a rather scruffy looking civilian). So I’d reckon that some older soldier tipped him off as to the ‘cheat’. Then off he went to a local seamstress, some coins changed hands, and she tacked in a dozen or so pleats in the right sort of place, so when Jock needed to get dressed in a hurry in a tent or his barrack-room bed space it was a simple matter and with no fiddling to arrange the pleats.

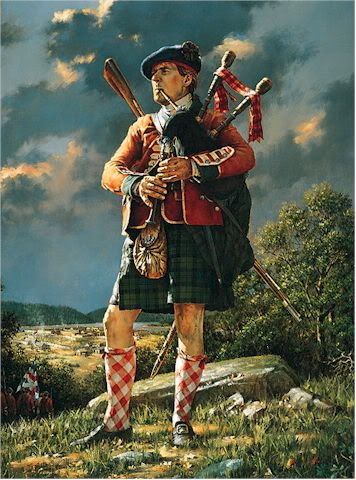

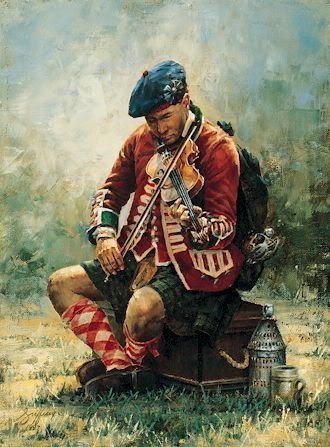

So what did he do with the fly? I think Griffing’s paintings are well researched – I don’t know what his sources were. In three of them (“One of their own”, “Major Grant’s Piper”, and “A long way from home”) the fly is discernible.

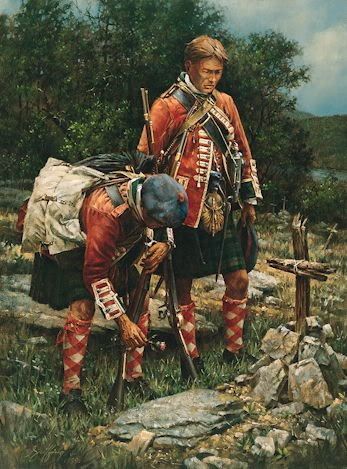

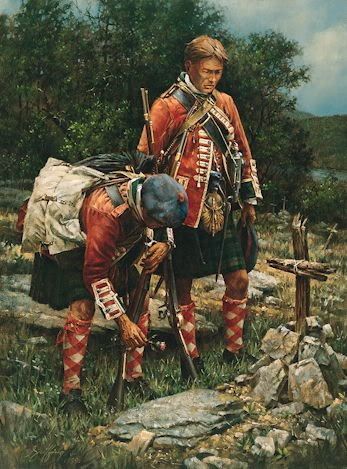

One of their own:

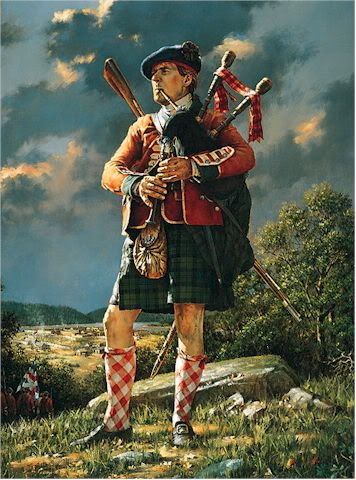

Major Grant's Piper:

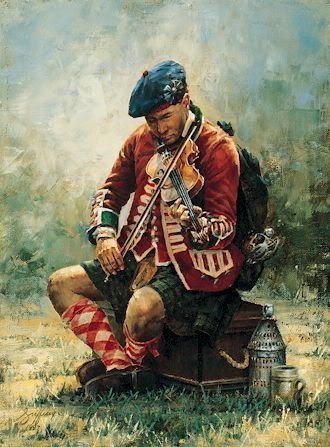

A Long Way from Home:

The right-hand part of the ‘train’ seems to be gathered up and tucked into something, or tied, by the left shoulder-blade (rather than passed over the shoulder and fixed by a brooch below the collar-bone). The left-hand part has probably been twisted, passed round the back, and tucked into the belt somewhere by the right hip leaving a bunch of cloth at the left thigh (perhaps to function as a pocket).

Can anyone shed light on this? I’m not really thinking about the art appreciation of Griffing’s work, which I like anyway, but the matter of arranging the train of the fèileadh mòr so that it looks smart enough and can be done simply.

-

Similar Threads

-

By CelticRanger66 in forum Miscellaneous Forum

Replies: 32

Last Post: 26th August 07, 04:41 AM

-

By David White in forum Miscellaneous Forum

Replies: 11

Last Post: 17th March 07, 02:57 PM

-

By auld argonian in forum Kilts in the Media

Replies: 0

Last Post: 3rd October 06, 02:19 PM

-

By Brasilikilt in forum General Kilt Talk

Replies: 18

Last Post: 16th October 05, 08:51 AM

-

By MACKAY in forum General Kilt Talk

Replies: 43

Last Post: 1st August 05, 06:56 AM

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

|

|

Bookmarks